The Latin American Foto Festival in New York City has one main goal: generate awareness about the current situation in Latin America and the opportunity for the wider community to witness and understand the diverse stories throughout the region.

The second edition of the annual photography exhibition, on display now through July 21, takes place on the streets of the South Bronx and at the Bronx Documentary Center.

Exhibition coordinator Cynthia Rivera and Michael Kamber, the director of the center, have curated everything carefully — including the neighborhood itself. It’s not a coincidence that the discussion happens at the heart one of the most important Latino communities in New York City — the Melrose neighborhood, streets where the Spanish language is often spoken by immigrants and their families.

The Latin American Foto Festival exhibits photographs and installations and also holds workshops and panel discussions, some of them in Spanish. This year’s nine featured photographers are award-winning professionals from throughout the Caribbean and Latin America, and nearly all of them live and work in their home countries.

Cimarrona

Nicole Carcelén, 19, is pictured with a cotton plant in her hair. The black slaves who first came to Ecuador were forced to work in cotton fields, cane fields and coal mines. For Nicole, cotton plants represent the strength of her ancestors. La Loma, 2018.

© Johis Alarcón

Cimarrona

Katherine Ramos, 23, is a member of the pan-African activist group Addis Ababa. Her grandmothers taught her about the use of turbans and she wears them as a loose crown. Quito, 2019.

© Johis Alarcón

Their works focus on political and economic crisis, migration, racism, discrimination, violence, corruption, and how women and Afro-Latino communities live.

“Many visitors tell us that they see the headlines in the newspapers or on social media,” Kamber told Global Citizen, adding that such stories often show statistics surrounding issues in Latin America. “But when they come to see an exhibition of photos driven by the photographers’ experiences — by family members migrated or killed or jailed or who are suffering from hunger and oppression — the news stories become very real and vital.”

Read More: 7 Things You Should Know About the Crisis in Venezuela

“I think it’s very important to generate empathy and connect the viewer to other people’s lives in other parts of the world,” he said.

And this year’s festival shows poetic images that are not simply traditional photojournalism.

La Ruta del Progreso, for instance, is a collaborative project between photographer Erika Rodriguez, visual artist Natalia Lasalle Morillo, and photographer Christopher Gregory, from Puerto Rico. The country has been facing major political and economic turmoil for about 10 years, facing the largest municipal debt crisis in the world, and was ravaged by a massive hurricane in 2018 that left nearly 3,000 people dead (some studies have estimated an even higher death toll).

La Ruta del Progreso.

La Ruta del Progreso.

Image: © Christopher Gregory

“La Ruta is a testament to the idea that to understand the current political reality, you have to look at the decisions that led to this point,” Gregory told Global Citizen. “In the case of Puerto Rico, it was trading an agricultural economy for an economy of colonial dependence with the United States, and it was a political system that has never enjoyed much autonomy. Puerto Rico, despite having locally elected officials in the executive and legislative branches, is basically overseen by a board appointed by the president of the United States, whom residents of Puerto Rico cannot vote for.”

Read More: Puerto Rico’s Crisis Is Not About ‘Broken Infrastructure.’ It’s About Poverty.

“Our main goal with the project is to look at the seminal moment of history of the 1950s when Puerto Rico was granted more autonomy and industrialized, through this road which was built during that time in the name of progress,” he added. “La Ruta does not necessarily make the case that progress did not arrive, but rather asks the viewer to make that determination. Progress, as the project documents in all its parts, is a loaded and complicated term.”

Another feature of the festival is Mestiza Women, a photo project that gives voice and images to contemporary Mexican women, according to photographer Citlali Fabián.

Mestiza

Nhawe, mi madre, 2017.

© Citlali Fabian

Mestiza

Eva, 2015.

© Citlali Fabian

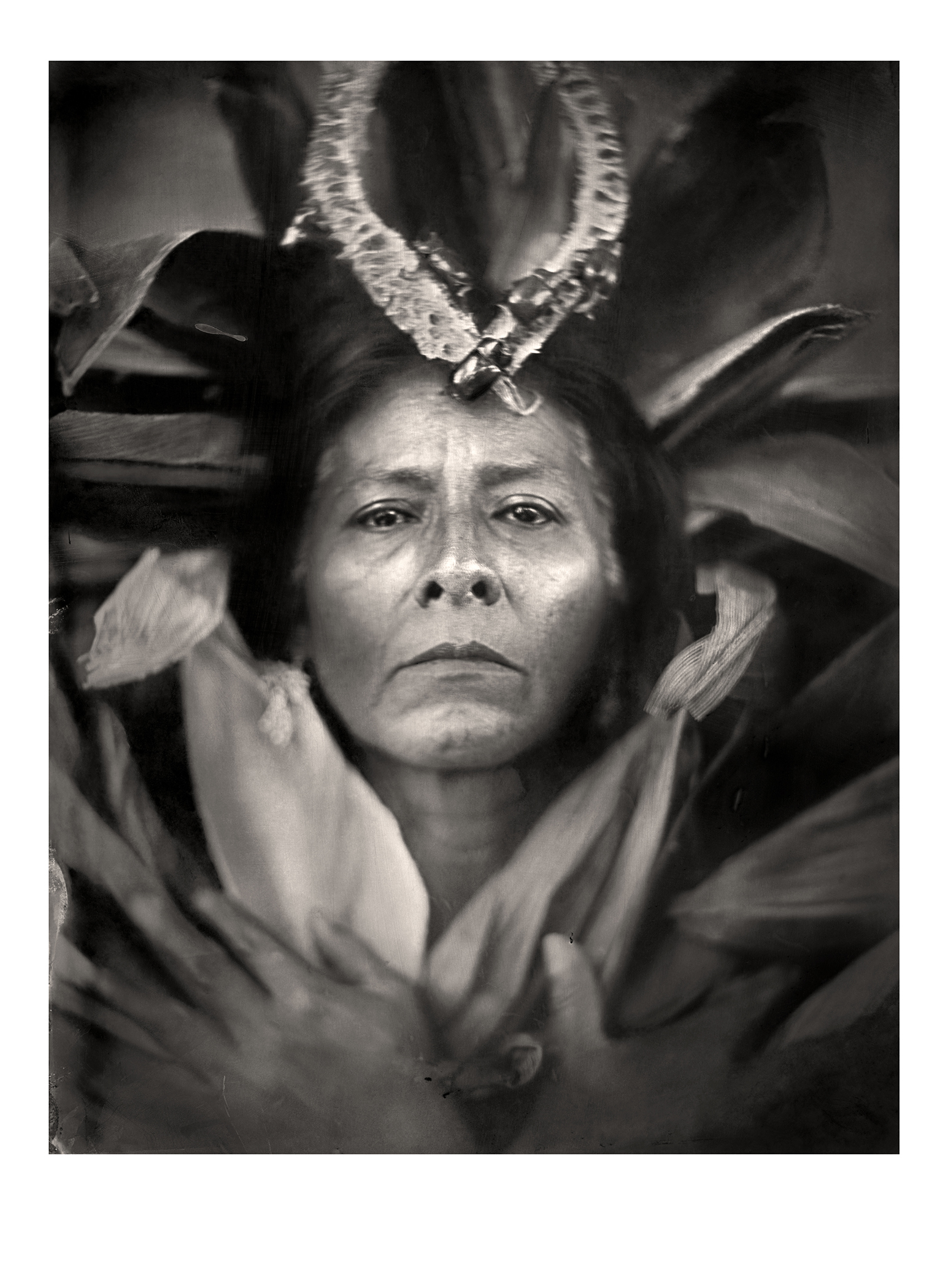

Mestiza

Cecilia, 2018.

© Citlali Fabian

“Mestiza was a term to refer to people who shared half Indigenous blood and half Caucasian blood,” Fabián told Global Citizen. “The term is a volatile mark to distinguish racial supremacy. This project attempts to glorify the variety of women within our mixed culture.”

In Mexico, she explained, whiteness has been held up as the standard of beauty for many years. To be a woman of color or Indigenous would “determine whether or not you’ll be discriminated [against] or a victim of violence,” she said.

“This project is a platform to rebuild ourselves, elevate our voices, and rethink the conception of our own body,” Fabián said.

Read More: UN Human Rights Chief Blasts Dire Conditions for Migrants at US Border

Fabián’s photos are made on glass with the 19th-century ambrotype process, and the women in her portraits are her family and friends.

“In order to appreciate the diversity of the world, it is necessary to understand that we are part of it. My artwork is the opportunity to open a dialogue to heal and embrace our identity, our origins, something completely necessary,” she said.

Tierra de Nadie.

Tierra de Nadie.

Image: © Luis Soto

The Latin American Foto Festival also focuses on Mexican and Central American photographers who explore the link between violence and migration.

Tierra de Nadie arises from the need to treat images as living documents of the memory of Guatemala. Photographer Luis Soto explained to Global Citizen that “it’s a big portrait of a country that is still in the fight to survive in an unequal and painful context.”

“Daily life in Guatemala is uncertain,” he said. “Poverty, racism, violence, exclusion, corruption are all problems that are part of the country and a context that never changed. Guatemala lived 36 years in a civil war and despite democracy and peace agreements, there are still powerful groups that remain in power and maintain this constant state of chaos and poverty.”

Blurred in Despair: Venezuela’s Psychological Turmoil

A group of people line up to buy one bag of rice per person in Caracas. That day, people were in the streets outside the store since 4 am, until a food truck arrived with rice. Only one per person is permitted.

© Fabiola Ferrero

Blurred in Despair: Venezuela’s Psychological Turmoil

A young protester waits for the water canon during an opposition demonstration that ended up in a 4 hour confrontation with the security forces in Caracas, April 6, 2017.

© Fabiola Ferrero

Photographer Johis Alarcon explores the cultural roots of Afro-Ecuadorian communities, and two exhibitions of Venezuelan photography expose the violence, poverty, and political upheaval that have driven an estimated 3 million people to flee their homeland in the largest mass migration in recent Latin American history.

Lee Más: 4 maneras en que la crisis de Venezuela está afectando la educación de los niños

“Latin America still has similar conflicts and problems, such as violence, poverty, migration crisis,” Soto said. “This festival allows a common voice that shouts, ‘We are here, and these are our problems,’ in order to transcend the media agenda and the global coverage.”

Image: © Andres Cardona

Image: © Andres Cardona

Family heart. “Photos on the wall of Perla Granda’s (my sister-in-law) bedroom of her missing brothers. She is 14 years old, she is in high school. She lives with her mother and Her sister Sandra at Taxco Guerrero Mexico.” Taken on September 10, 2013.

Family heart. “Photos on the wall of Perla Granda’s (my sister-in-law) bedroom of her missing brothers. She is 14 years old, she is in high school. She lives with her mother and Her sister Sandra at Taxco Guerrero Mexico.” Taken on September 10, 2013.

Image: © Yael Martinez V.

Source: Global Citizen